By Alan K. Lee

Many of us that live in the Pacific Northwest have a connection of one kind or another to the state of Arizona. Many Northwest retirees, like my parents, become snowbirds, escaping the Northwest winters by spending the colder months in the sunnier and warmer climes of the desert Southwest. Others, like my brother, escape at an earlier age. Most of the rest of us have vacationed at least once in Arizona, or at least have dreamed of doing so. My wife and I have both lived in the Pacific Northwest all our lives, but we’ve made many trips to Arizona over the years. One of our favorite places is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West.

Taliesin West is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most iconic creations. Begun in the same year that Falling Water, arguably his greatest creation, was built, Taliesin West was Wright’s winter home for the last two decades of his life.

Taliesin West was founded as the winter home for the Frank Lloyd Wright Fellowship, Wright’s school of architecture. It was always a school of architecture as well as Wright’s winter home. The Fellowship evolved into the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, which conducted classes at Taliesin West until 2020, when it separted from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, changed its name to The School of Architecture, and moved its campus to Cosanti and Arcosanti, Arizona.

Taliesin West was founded as the winter home for the Frank Lloyd Wright Fellowship, Wright’s school of architecture. It was always a school of architecture as well as Wright’s winter home. The Fellowship evolved into the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, which conducted classes at Taliesin West until 2020, when it separted from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, changed its name to The School of Architecture, and moved its campus to Cosanti and Arcosanti, Arizona.

Wright’s designs and his design philosophy had a profound impact on American architecture. He is without question the most famous American architect, by a wide margin. Ask anyone to name an architect and almost all, if they can name any, will name Wright.

Wright first achieved fame shortly after the turn of the 20th century for his Prairie House residential designs, and he was always more interested in designing homes for people than structures for businesses or government agencies. During the Great Depression he designed a planned community that featured simple, affordable residences that he called Usonian homes. Although his planned community was never built, many Usonian homes were. One of those, the Gordon House, is now located at the Oregon Garden in Silverton, Oregon, not far from my home.

![]()

Over his long career, Wright designed more than 1100 structures, 532 of which were built. But as famous and influential as he was, for much of his career he received few commissions. In the 1920s he made most of his income from writing and lecturing, rather than from his designs.

In 1932 Wright formed the Taliesin Fellowship, an apprenticeship program that taught not just architectural design, but also construction and “farming, gardening, and cooking, and the study of nature, music, art, and dance” according to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation website.

The original Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, was Wright’s primary residence for most of his life and also served as the campus of the Taliesin Fellowship. In 1934, to escape the often brutal weather in Wisconsin, Wright began taking his students to Arizona each winter.

Taliesin West began as the winter camp for Wright and his students. And it was an actual camp in the beginning. The students lived in tents for their first few winters in Arizona, and Taliesin West was an ongoing project for many years. Even after most of the structures were completed, for example, all of the windows were simply openings in the walls, without glass, for almost a decade.

Wright’s design philosophy was holistic, and humanistic. He saw houses as organic structures that should be built in harmony with their environment and in tune with their inhabitants. “It is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another,” he wrote. He believed that all had to work “as one thing.” There is a story, whether true or not I don’t know, that the purchasers of one of his early residential designs invited him to their home after they moved in and he was so appalled by the way they had furnished the home that from that point on he not only designed the structures, he designed all of the furniture (much of it built in), the lighting, the rugs, the artwork, and even the dinnerware that went into them.

Wright’s design philosophy was holistic, and humanistic. He saw houses as organic structures that should be built in harmony with their environment and in tune with their inhabitants. “It is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another,” he wrote. He believed that all had to work “as one thing.” There is a story, whether true or not I don’t know, that the purchasers of one of his early residential designs invited him to their home after they moved in and he was so appalled by the way they had furnished the home that from that point on he not only designed the structures, he designed all of the furniture (much of it built in), the lighting, the rugs, the artwork, and even the dinnerware that went into them.

The structures at Taliesin West reflect Wright’s belief that architecture must reflect the natural setting of the site. To that end, they were built using native stone and other materials harvested from the site. That, and the long, horizontal orientation and flat roofed construction help them blend almost seamlessly into the environment. Taliesin West would still be a beautiful and striking piece of architecture even if it was located elsewhere, but it would not be as in harmony with its setting as it is, and it would be a lesser work.

The grounds of Taliesin West are beautifully landscaped and feature many outdoor works of art by various artists. Wright saw architecture as the “mother” of all the arts, and art was an important component of his designs, as was the landscaping.

The grounds of Taliesin West are beautifully landscaped and feature many outdoor works of art by various artists. Wright saw architecture as the “mother” of all the arts, and art was an important component of his designs, as was the landscaping.

Wright’s work ensures his place in history as one of the architectural greats. Today, Taliesin West lives on as testament to that greatness, and as home to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Taliesin West is located in Scottsdale, Arizona, about 20 miles northeast of downtown Phoenix.

Taliesin West is located in Scottsdale, Arizona, about 20 miles northeast of downtown Phoenix.

Originally posted November 26, 2019. Updated and re-posted January 7, 2022.

Originally posted November 26, 2019. Updated and re-posted January 7, 2022.

All photos © Alan K. Lee

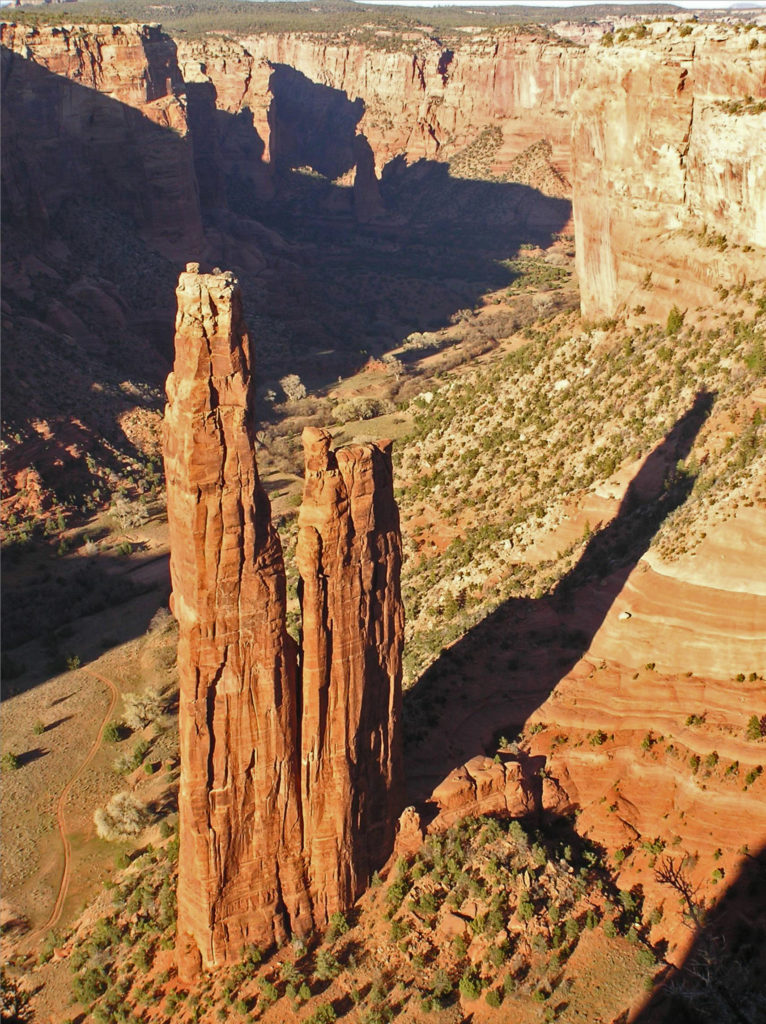

The name Chelly comes from the Spanish spelling of the Navajo name for canyon, tseyi, which translates literally as “within the rock.” Over time the Spanish pronunciation, “chay-ee”, has evolved into the current pronunciation, “shay”.

The name Chelly comes from the Spanish spelling of the Navajo name for canyon, tseyi, which translates literally as “within the rock.” Over time the Spanish pronunciation, “chay-ee”, has evolved into the current pronunciation, “shay”.

Located a couple of miles east of Chinle, Arizona, the monument’s Welcome Center is a good place to start your visit. Pick up a free map of the monument and watch a short film about the monument to orient yourself. The park rangers can answer any questions you have about tours of the canyon, accommodations, the canyon’s history or geology, what plants and animals you’ll find in the park, or any other questions you might have. There is also a gift shop where souvenirs of your visit can be purchased.

Located a couple of miles east of Chinle, Arizona, the monument’s Welcome Center is a good place to start your visit. Pick up a free map of the monument and watch a short film about the monument to orient yourself. The park rangers can answer any questions you have about tours of the canyon, accommodations, the canyon’s history or geology, what plants and animals you’ll find in the park, or any other questions you might have. There is also a gift shop where souvenirs of your visit can be purchased.

Canyon de Chelly is worth a visit just for the spectacular scenery it affords, but it is also an important cultural and historic site. The canyon is one of the longest continuously inhabited places in North America. The Ancestral Puebloans (also known as the Anasazi) first settled in the area some 4,000 years ago. The canyon was later occupied by the Hopi, descendents of the Ancestral Puebloans, and more recently by the Navaho.

Canyon de Chelly is worth a visit just for the spectacular scenery it affords, but it is also an important cultural and historic site. The canyon is one of the longest continuously inhabited places in North America. The Ancestral Puebloans (also known as the Anasazi) first settled in the area some 4,000 years ago. The canyon was later occupied by the Hopi, descendents of the Ancestral Puebloans, and more recently by the Navaho.

Originally posted May 14, 2020. Updated and re-posted February 14, 2022.

Originally posted May 14, 2020. Updated and re-posted February 14, 2022.

Originally posted April 28, 2020. Edited, updated, and re-posted February 5, 2022

Originally posted April 28, 2020. Edited, updated, and re-posted February 5, 2022

There is so much here that you probably can’t see it all in one visit. My wife and I have visited the museum on a couple of our Arizona excursions, and on our last visit I was surprised at how much I had missed on our earlier visit. Plan to spend at least two hours at the museum. Allow half a day to more fully explore what the museum has to offer, if you can.

There is so much here that you probably can’t see it all in one visit. My wife and I have visited the museum on a couple of our Arizona excursions, and on our last visit I was surprised at how much I had missed on our earlier visit. Plan to spend at least two hours at the museum. Allow half a day to more fully explore what the museum has to offer, if you can.

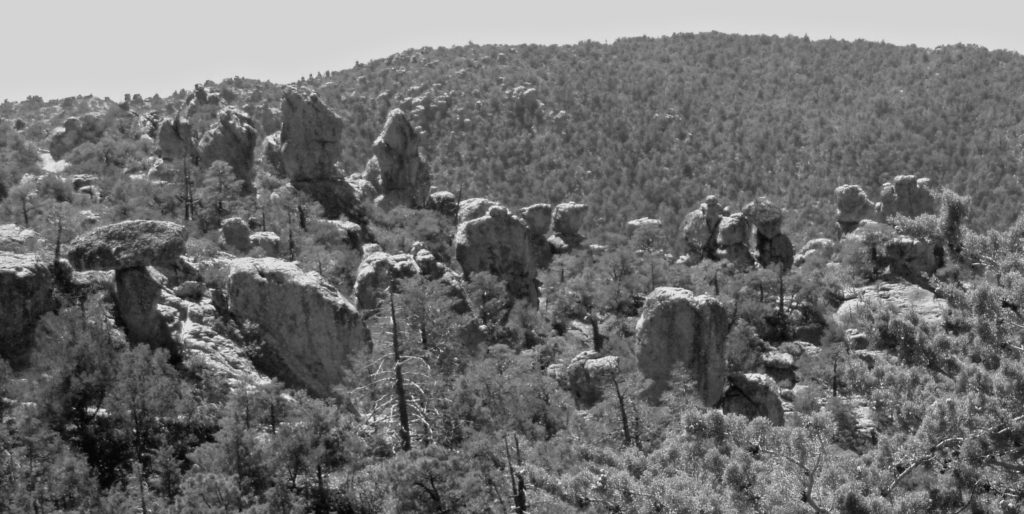

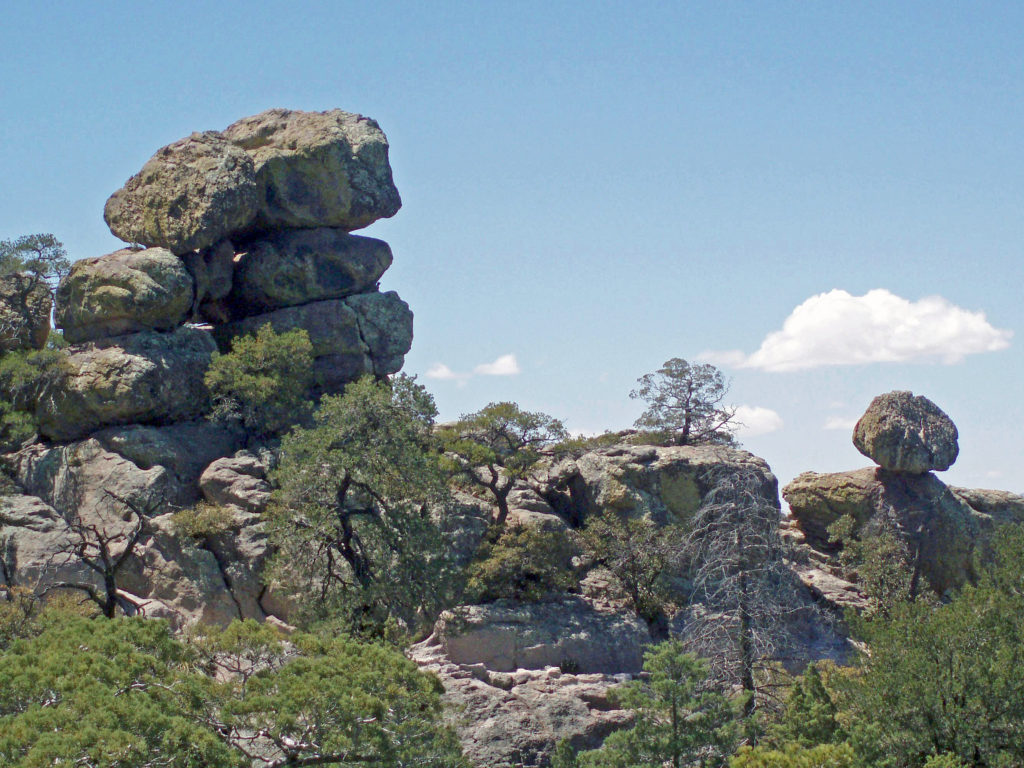

If you’re ever in the Tucson area, consider making the drive to the top of Mount Lemmon. A paved road takes you to the summit, more than 6500 feet above the valley floor. Numerous viewpoints along the way provide spectacular vistas of the mountain, the surrounding desert below, and the mountains beyond. And numerous trailheads provide access to the ridges and canyons beyond the road for those who want to lace up their hiking boots and immerse themselves in the desert or mountain environment.

If you’re ever in the Tucson area, consider making the drive to the top of Mount Lemmon. A paved road takes you to the summit, more than 6500 feet above the valley floor. Numerous viewpoints along the way provide spectacular vistas of the mountain, the surrounding desert below, and the mountains beyond. And numerous trailheads provide access to the ridges and canyons beyond the road for those who want to lace up their hiking boots and immerse themselves in the desert or mountain environment. The drive takes you through numerous climatic and ecological zones, from the iconic saguaro cactus of the Sonoran Desert at the base of the mountain to an aspen and ponderosa pine forest at the summit.

The drive takes you through numerous climatic and ecological zones, from the iconic saguaro cactus of the Sonoran Desert at the base of the mountain to an aspen and ponderosa pine forest at the summit. My wife and I made the drive to the summit in October 2019 while in Arizona to visit my brother and attend a wedding. I had never heard of Mount Lemmon and I wasn’t keen on making that long of a side trip, but my wife convinced me that it would be worthwhile, and she nailed this one. Mount Lemmon is more than just worthwhile, and worth more than just a side trip. It’s a worthy destination in its own right.

My wife and I made the drive to the summit in October 2019 while in Arizona to visit my brother and attend a wedding. I had never heard of Mount Lemmon and I wasn’t keen on making that long of a side trip, but my wife convinced me that it would be worthwhile, and she nailed this one. Mount Lemmon is more than just worthwhile, and worth more than just a side trip. It’s a worthy destination in its own right.

Windy Point, about seventeen miles from the beginning of the highway in Tanque Verde, has got to be one of the most spectacular viewpoints in southern Arizona. You’ll want to stop here and just wander around for a while. Take in the views of Tucson and the desert far below, the mountains beyond, and the rock formations around you. About four miles farther up the highway you’ll come to the San Pedro Vista, which gives you a panoramic view east across the San Pedro Valley to the Galiuro Mountains.

Windy Point, about seventeen miles from the beginning of the highway in Tanque Verde, has got to be one of the most spectacular viewpoints in southern Arizona. You’ll want to stop here and just wander around for a while. Take in the views of Tucson and the desert far below, the mountains beyond, and the rock formations around you. About four miles farther up the highway you’ll come to the San Pedro Vista, which gives you a panoramic view east across the San Pedro Valley to the Galiuro Mountains. Another couple miles brings you to the

Another couple miles brings you to the

If you go, note that the summit of Mount Lemmon can be thirty degrees cooler than Tucson, so dress accordingly. And if you plan to do any hiking, avoid mid-summer if possible and always bring plenty of water. There are no sources of safe drinking water on any of the hiking trails in the area, to my knowledge.

If you go, note that the summit of Mount Lemmon can be thirty degrees cooler than Tucson, so dress accordingly. And if you plan to do any hiking, avoid mid-summer if possible and always bring plenty of water. There are no sources of safe drinking water on any of the hiking trails in the area, to my knowledge.

Not only am I glad we took the drive, I wish we could have spent more time exploring the mountain. For those that do have the time, there are several picnic areas along the highway and a few places to eat in Summerhaven, and there are several campgrounds a short ways off of the highway if you want to spend more than a day on the mountain. If you don’t want to camp, Summerhaven also has a few rental cabins, and a newly built small hotel. Check the

Not only am I glad we took the drive, I wish we could have spent more time exploring the mountain. For those that do have the time, there are several picnic areas along the highway and a few places to eat in Summerhaven, and there are several campgrounds a short ways off of the highway if you want to spend more than a day on the mountain. If you don’t want to camp, Summerhaven also has a few rental cabins, and a newly built small hotel. Check the  Note: In the summer of 2020 the entire area was closed to the public because of the Bighorn Fire that burned 120,000 acres in the Santa Catalina Mountains. Photos taken after the fire showed some badly burned areas, but others that were largely untouched. All of the area is open again, including the Palisades Visitor Center.

Note: In the summer of 2020 the entire area was closed to the public because of the Bighorn Fire that burned 120,000 acres in the Santa Catalina Mountains. Photos taken after the fire showed some badly burned areas, but others that were largely untouched. All of the area is open again, including the Palisades Visitor Center.