Located between the small towns of Manzanita and Cannon Beach on the north Oregon coast, Oswald West State Park offers a beautiful secluded beach, a prime example of spruce-hemlock temperate rain forest, and some of the most spectacular scenery on the entire coast. The park stretches from Arch Cape in the north to the south slopes of Neahkahnie Mountain, with Smugglers Cove and Short Sand Beach nestled in between Cape Falcon and the north flank of Neahkahnie Mountain.

Oswald West State Park has long been one of my favorite destinations on the Oregon coast. On one of my recent visits, a few days before the spring equinox, the sun was shining, there was an off shore breeze blowing, and the temperature on the beach was about 75 degrees. It was one of those beautiful late winter/early spring breakout days that signal the end of winter – a near perfect day for hiking, sight seeing, and just relaxing on the beach.

The park, originally called Short Sand Beach State Park, was created in 1931 through the efforts of Oregon’s first State Parks Superintendent, Samuel H. Boardman. Boardman was a fervent believer that of as much of the coast should be preserved in public ownership as possible. Many of the state parks along the coast were created under his stewardship. Short Sand Beach State Park was renamed in 1958 to honor former Oregon Governor Oswald West (1873-1960). West was instrumental in preserving public ownership of all Oregon beaches during his term in office (1911-1915) .

The park, originally called Short Sand Beach State Park, was created in 1931 through the efforts of Oregon’s first State Parks Superintendent, Samuel H. Boardman. Boardman was a fervent believer that of as much of the coast should be preserved in public ownership as possible. Many of the state parks along the coast were created under his stewardship. Short Sand Beach State Park was renamed in 1958 to honor former Oregon Governor Oswald West (1873-1960). West was instrumental in preserving public ownership of all Oregon beaches during his term in office (1911-1915) .

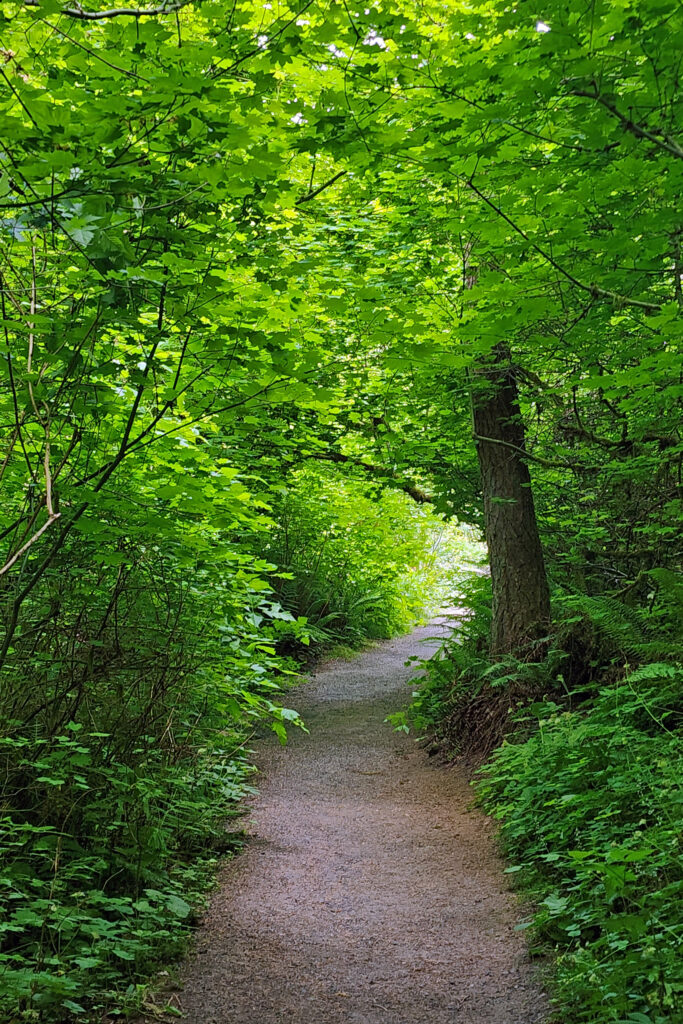

Short Sand Beach (also known as Short Sands Beach or just Shorty’s) is popular with local surfers, and is also a popular family destination. The three paved parking lots along Hwy 101 are often full on summer weekends. The short trail to the beach takes you through through the temperate rain forest along Short Sand Creek. There was a walk-in campground located in the forest adjacent to the south end of the beach until 2008 when a large Sitka spruce fell without warning, crushing two fortunately unoccupied campsites. The campground was permanently closed after examination of other trees revealed that several more were in danger of falling.

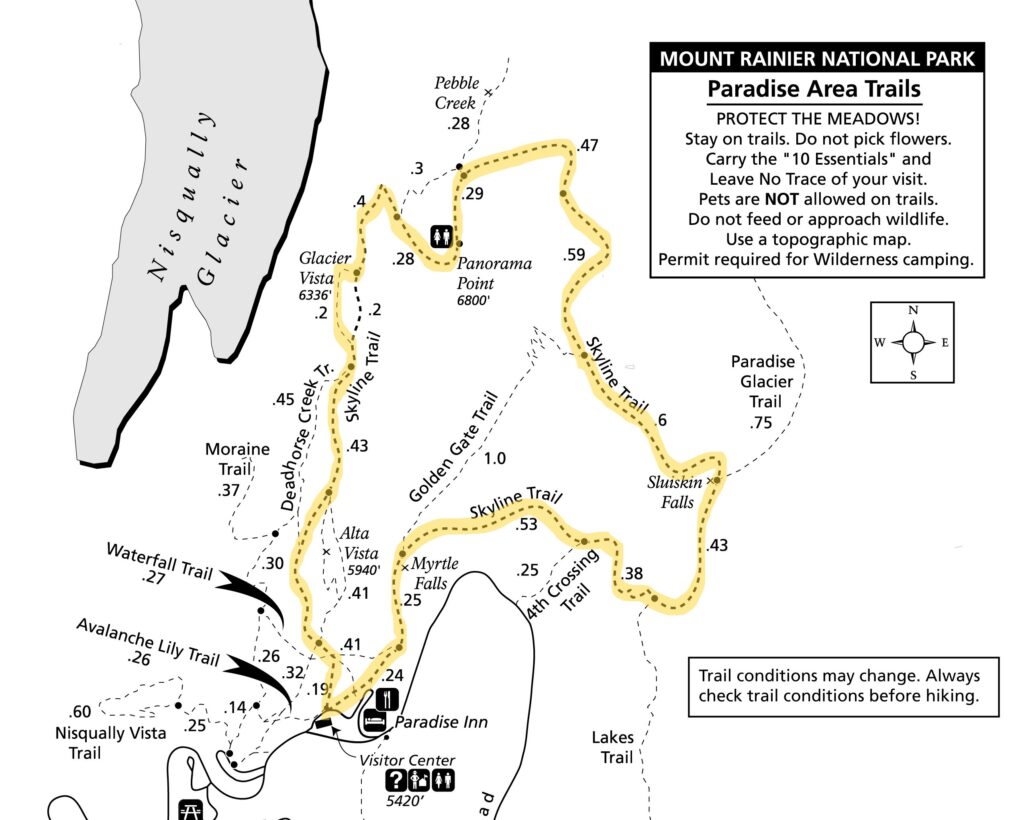

There are many miles of hiking trails within the park, including thirteen miles of the iconic Oregon Coast Trail. The Oswald West State Park trail guide is a good reference for hikers. Cape Falcon and the north slopes of Neahkahnie Mountain both offer truly spectacular scenery, and can be accessed from Short Sand Beach. The Cape Falcon trail is a personal favorite of mine. Most people don’t venture beyond Short Sand Beach, so you are likely to find yourself with little company, particularly on the section of trail between Cape Falcon and Arch Cape. The trail winds through the spruce-hemlock forest and over Cape Falcon with numerous viewpoints looking south across Smugglers Cove to Neahkahnie Mountain. North of Cape Falcon the trail passes through more spruce-hemlock forest to the small community of Arch Cape, just north of the Arch Cape headland.

Devils Cauldron is a spectacularly beautiful little cove on the north side of Neahkahnie Mountain. It can be reached by either a one mile hike from Short Sand Beach or a much shorter hike from where the Coast Trail crosses Hwy 101. To access the shorter route, drive south on Hwy 101 from the Short Sand Beach parking lots and look for a gravel parking area on the ocean side of the highway. Follow the Coast Trail north a short ways to a signed junction. The Devils Cauldron viewpoint is just a quarter mile walk from the parking area.

Devils Cauldron is a spectacularly beautiful little cove on the north side of Neahkahnie Mountain. It can be reached by either a one mile hike from Short Sand Beach or a much shorter hike from where the Coast Trail crosses Hwy 101. To access the shorter route, drive south on Hwy 101 from the Short Sand Beach parking lots and look for a gravel parking area on the ocean side of the highway. Follow the Coast Trail north a short ways to a signed junction. The Devils Cauldron viewpoint is just a quarter mile walk from the parking area.

On your way back to the trailhead look for another trail branching off to the south. The junction here is unsigned and the trail is sometimes overgrown and impassable. But if it’s open, the trail leads to a narrow shelf of rock that falls away on three sides to the ocean below, and the cliffs of Neahkahnie Mountain tower over the viewpoint to both the north and south. It may not be a place for people with a fear of heights, but it’s one of the most awesome places on the entire coast.

On your way back to the trailhead look for another trail branching off to the south. The junction here is unsigned and the trail is sometimes overgrown and impassable. But if it’s open, the trail leads to a narrow shelf of rock that falls away on three sides to the ocean below, and the cliffs of Neahkahnie Mountain tower over the viewpoint to both the north and south. It may not be a place for people with a fear of heights, but it’s one of the most awesome places on the entire coast.

If you’re not a hiker, Hwy 101 has numerous turnouts along the stretch that traverses the face of Neahkahnie Mountain. Here the highway is literally carved into the cliff high above the sea. The views of the ocean and coastline are truly spectacular, and Neahkahnie is one of the best places to spot gray whales.

In the spring, about 18,000 gray whales make the annual trek from their breeding grounds in Baja California to feed in the nutrient rich waters off Alaska. At the peak of the migration in late March about 30 whales per hour pass any given spot on the Oregon coast. Oregon State Parks sponsors Whale Watch Week twice each year, in late March and again in late December when the whales are returning to Baja. Volunteers can be found at 17 spots along the coast, including Neahkahnie Mountain, to help you spot migrating whales. Check the Oregon State Parks Whale Watching website for more information.

After visiting Oswald West, I like to stop at Cannon Beach or Manzanita for a bite to eat and/or a brew or two. In Cannon Beach try Oro’s Fireside Restaurant, Corbin’s, Castaways Global Cuisine, or Pizza A’ Fetta. Cannon Beach brew pubs worth visiting include Pelican Brewing, Bill’s Tavern and Brewhouse, and Public Coast Brewing. If you’re looking for fine dining and cost is not an issue, try the Stephanie Inn or Newmans At 988.

If you’re heading south, Big Wave Cafe, Left Coast Siesta (Mexican), Neah-kah-nie Bistro (fine dining), Marzano’s Pizza Pie, and San Dune Pub (that’s not a typo) in Manzanita are all good places to stop, as is Riverside Fish and Chips in nearby Nehalem. A good breakfast before heading to the park can be had at Lazy Susan Cafe in Cannon Beach, Yolk in Manzanita, or Wanda’s Cafe in Nehalem.

Oswald West State Park is about a two hour drive from Portland, so it’s easily doable as a day trip if you’re from the Portland area or are visiting Portland. But if you want to make a weekend of it, there are plenty of other attractions on the north Oregon coast beyond Oswald West. Hug Point is another spot that my wife and I visit frequently. Both Manzanita and Cannon Beach are interesting towns worth exploring in their own right, have nice beaches, and have many resorts, motels, B&Bs, and other accommodations, as well as their many fine eating and drinking establishments. Seaside, Gearhart, and the Astoria area are other options to the north. Public campgrounds can be found at Nehalem Bay State Park near Manzanita (265 camp sites and 18 yurts), and Fort Stevens State Park (almost 500 campsites, 15 yurts and 11 cabins) at the mouth of the Columbia River about 30 miles north of Oswald West.

Oswald West State Park is about a two hour drive from Portland, so it’s easily doable as a day trip if you’re from the Portland area or are visiting Portland. But if you want to make a weekend of it, there are plenty of other attractions on the north Oregon coast beyond Oswald West. Hug Point is another spot that my wife and I visit frequently. Both Manzanita and Cannon Beach are interesting towns worth exploring in their own right, have nice beaches, and have many resorts, motels, B&Bs, and other accommodations, as well as their many fine eating and drinking establishments. Seaside, Gearhart, and the Astoria area are other options to the north. Public campgrounds can be found at Nehalem Bay State Park near Manzanita (265 camp sites and 18 yurts), and Fort Stevens State Park (almost 500 campsites, 15 yurts and 11 cabins) at the mouth of the Columbia River about 30 miles north of Oswald West.

If you’re an art lover, Cannon Beach has many fine art galleries, including White Bird, DragonFire, Bronze Coast, Jeffrey Hull, North By Northwest, Imprint, and Icefire Glassworks. Look for a future Pacific Northwest Explorer post on the Cannon Beach art scene.

Originally posted March 27, 2019 by Alan K. Lee. Updated and re-posted June 26, 2021 and November 4, 2023.

All photos © Alan K. Lee

Overview:

Overview: Getting there:

Getting there: Trailhead:

Trailhead: The hike:

The hike: The Townsite Trail takes you along the river through a mixed woodland of Douglas fir, bigleaf maple, and red alder with partially screened views of the river. There are several user-made trails leading down to the water, but they are steep (and dangerous if the ground is wet), so be careful if you want to get to the water for a better view of the river.

The Townsite Trail takes you along the river through a mixed woodland of Douglas fir, bigleaf maple, and red alder with partially screened views of the river. There are several user-made trails leading down to the water, but they are steep (and dangerous if the ground is wet), so be careful if you want to get to the water for a better view of the river. At about the one-mile mark you’ll come to an open field on your right and you’ll see a boat dock ahead on your left. There is a small parking area here with a restroom. Head down to the dock for the best views of the river on this hike.

At about the one-mile mark you’ll come to an open field on your right and you’ll see a boat dock ahead on your left. There is a small parking area here with a restroom. Head down to the dock for the best views of the river on this hike.

Coming back up from the dock, look for a trail to your left. This will take you to Champoeg Creek where it flows into the Willamette. The trail then loops back through the forest and comes out into a clearing. Follow the edge of the clearing back to the restroom above the dock. From there, retrace your route back to the trailhead at the Riverside picnic area.

Coming back up from the dock, look for a trail to your left. This will take you to Champoeg Creek where it flows into the Willamette. The trail then loops back through the forest and comes out into a clearing. Follow the edge of the clearing back to the restroom above the dock. From there, retrace your route back to the trailhead at the Riverside picnic area. Best time to go:

Best time to go: Champoeg State Park:

Champoeg State Park:

Posted October 26, 2023 by Alan K. Lee

Posted October 26, 2023 by Alan K. Lee

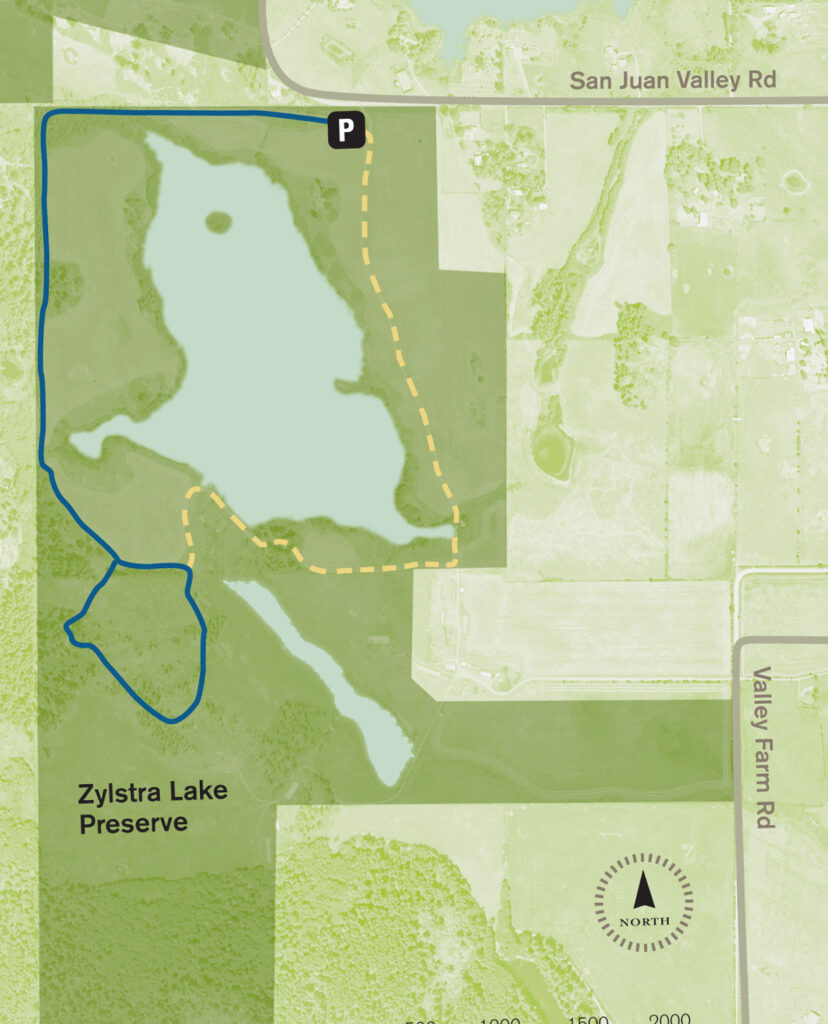

The property was formerly a privately owned farm that was the site of a proposed housing development. Instead, the property was sold to the land bank in 2015 and the trust obtained the conservation easement. Thirty acres of the property, including the farmhouse and agricultural buildings, were sold by the land bank to Island Haven, a non-profit animal sanctuary, with a conservation easement to protect the land.

The property was formerly a privately owned farm that was the site of a proposed housing development. Instead, the property was sold to the land bank in 2015 and the trust obtained the conservation easement. Thirty acres of the property, including the farmhouse and agricultural buildings, were sold by the land bank to Island Haven, a non-profit animal sanctuary, with a conservation easement to protect the land. Currently, there is no public access to the lakeshore, and the eastern and southern portions of the trail around the lake are closed from October through March. The northern and western portions of the loop are open year-round and can be hiked as a lollipop loop during the winter.

Currently, there is no public access to the lakeshore, and the eastern and southern portions of the trail around the lake are closed from October through March. The northern and western portions of the loop are open year-round and can be hiked as a lollipop loop during the winter.

Getting there:

Getting there: Trailhead:

Trailhead: The hike:

The hike:

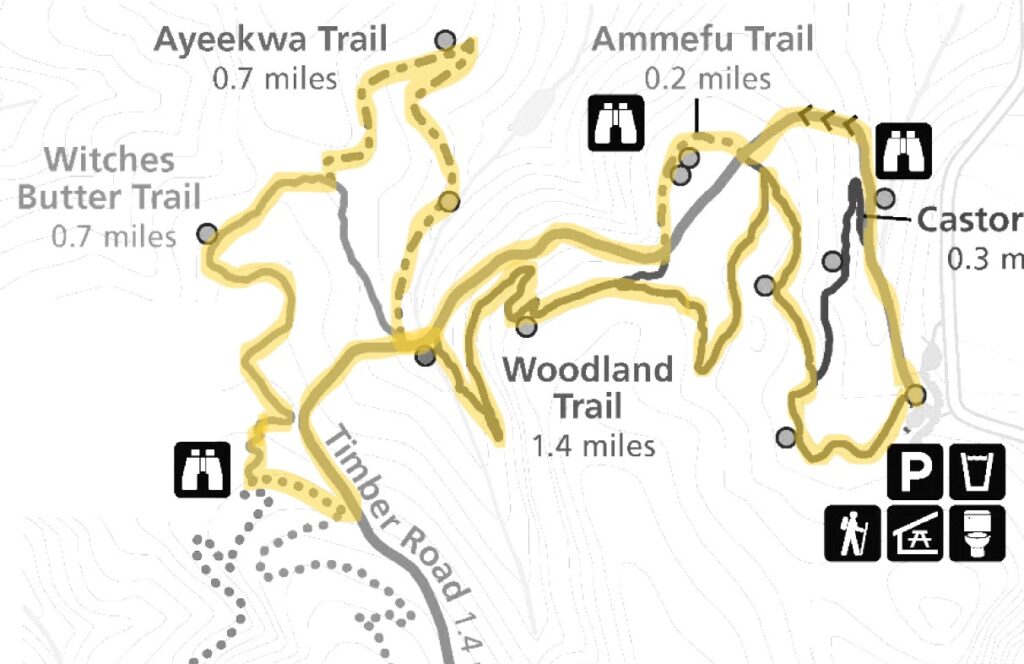

At 0.3 miles the trail turns south and runs along the western boundary of the preserve for another 0.4 miles. The trail then turns southeast and follows the edge of an open field with good views of the lake.

At 0.3 miles the trail turns south and runs along the western boundary of the preserve for another 0.4 miles. The trail then turns southeast and follows the edge of an open field with good views of the lake.

At the 0.85-mile mark, turn right onto a trail that leads through a mix of open fields and partially logged woodland.

At the 0.85-mile mark, turn right onto a trail that leads through a mix of open fields and partially logged woodland. At the 1.25-mile mark, the trail returns to the open field. In winter, the trail ahead is closed, so you need to turn left and retrace your route back to the trailhead parking area.

At the 1.25-mile mark, the trail returns to the open field. In winter, the trail ahead is closed, so you need to turn left and retrace your route back to the trailhead parking area. In summer, you can continue straight. The trail then turns right and crosses a bridge over the creek that flows from the lake. Beyond the bridge, the trail runs along the top of the dam that forms the lake, then passes through a small grove of trees.

In summer, you can continue straight. The trail then turns right and crosses a bridge over the creek that flows from the lake. Beyond the bridge, the trail runs along the top of the dam that forms the lake, then passes through a small grove of trees. From there, the trail runs between fields to the old farmhouse site that is now home to the Island Haven animal sanctuary. The trail turns left there and follows a gravel farm road back to the trailhead.

From there, the trail runs between fields to the old farmhouse site that is now home to the Island Haven animal sanctuary. The trail turns left there and follows a gravel farm road back to the trailhead.

Posted October 12, 2023 by Alan K. Lee

Posted October 12, 2023 by Alan K. Lee

There is no shortage of places to eat in Friday Harbor. For breakfast and lunch, I can personally recommend both Rocky Bay Café and Tina’s Place. For dining with a view, go to Downriggers on the bayfront. Classic Italian food can be found at Vinny’s Ristorante. Vegetarian and vegan food can be had at Mike’s Café and Wine Bar. For quality craft beers and upscale pub food, try San Juan Brewing. For seafood in a casual dining space, check out Friday’s Crab House. We ate at all of those, and all were good. But that’s just a sampling of what Friday Harbor offers. I wish we had had a few more days to sample more of the town’s eateries. What’s a vacation for, after all.

There is no shortage of places to eat in Friday Harbor. For breakfast and lunch, I can personally recommend both Rocky Bay Café and Tina’s Place. For dining with a view, go to Downriggers on the bayfront. Classic Italian food can be found at Vinny’s Ristorante. Vegetarian and vegan food can be had at Mike’s Café and Wine Bar. For quality craft beers and upscale pub food, try San Juan Brewing. For seafood in a casual dining space, check out Friday’s Crab House. We ate at all of those, and all were good. But that’s just a sampling of what Friday Harbor offers. I wish we had had a few more days to sample more of the town’s eateries. What’s a vacation for, after all.

Near Roche Harbor (I think it’s actually part of the resort), the San Juan Islands Sculpture Park is a must see if you’re at all interested in sculpture. There are over 100 works of art (it seemed like many more) spread out over the twenty acres of the garden. Plan to spend at least an hour here. We spent more than that and still didn’t see it all. Admission is free, but donations are requested.

Near Roche Harbor (I think it’s actually part of the resort), the San Juan Islands Sculpture Park is a must see if you’re at all interested in sculpture. There are over 100 works of art (it seemed like many more) spread out over the twenty acres of the garden. Plan to spend at least an hour here. We spent more than that and still didn’t see it all. Admission is free, but donations are requested.

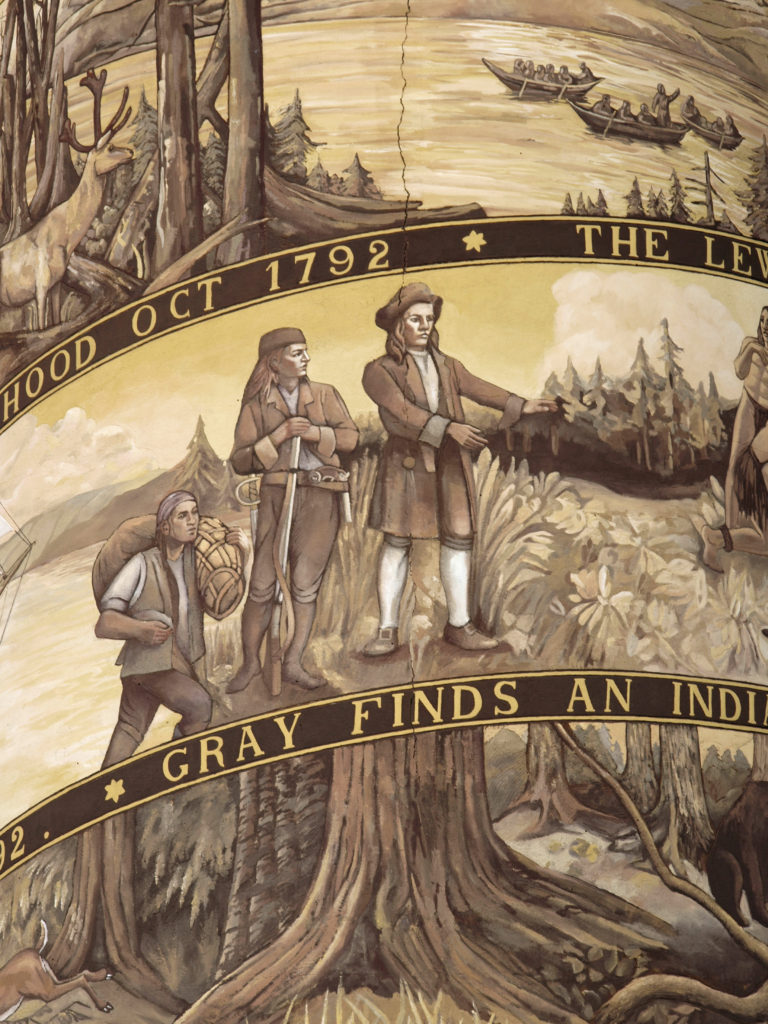

Tensions between the American and British contingents led both England and the U.S. to send military forces to the island. From 1859 to 1872, when the boundary dispute was finally settled in favor of the United States, the island was jointly occupied by both forces. No actual combat occurred, and no one was injured in the Pig War. The sites of the two country’s military installations are now part of

Tensions between the American and British contingents led both England and the U.S. to send military forces to the island. From 1859 to 1872, when the boundary dispute was finally settled in favor of the United States, the island was jointly occupied by both forces. No actual combat occurred, and no one was injured in the Pig War. The sites of the two country’s military installations are now part of

Conclusion

Conclusion

Posted October 12, 2023 by Alan K. Lee

Posted October 12, 2023 by Alan K. Lee

Hosmer Lake is a mix of open water and reeds, rushes, water lilies, and other marsh plants. Motorized craft (except for electric motor powered) are not allowed on the lake, which makes it ideal for kayaking or canoeing. It’s also not a big lake at 160 acres, so you can easily explore it all in an afternoon.

Hosmer Lake is a mix of open water and reeds, rushes, water lilies, and other marsh plants. Motorized craft (except for electric motor powered) are not allowed on the lake, which makes it ideal for kayaking or canoeing. It’s also not a big lake at 160 acres, so you can easily explore it all in an afternoon.

Hosmer Lake is fed by Quinn Creek, which flows into the north end of the lake. Quinn Creek is narrow and shallow, but it is possible to paddle up it for a ways. When we were there last, downed trees blocked our passage a few hundred yards from the mouth of the creek. We hauled our kayaks out of the water at that point and hiked along the creek to a small waterfall where we ate lunch and lingered awhile before heading back out on the water.

Hosmer Lake is fed by Quinn Creek, which flows into the north end of the lake. Quinn Creek is narrow and shallow, but it is possible to paddle up it for a ways. When we were there last, downed trees blocked our passage a few hundred yards from the mouth of the creek. We hauled our kayaks out of the water at that point and hiked along the creek to a small waterfall where we ate lunch and lingered awhile before heading back out on the water. Recalling our visits to Hosmer Lake, I’m eager now to get back to the area and get back on the water again. It’s a beautiful place, and one of my favorite destinations.

Recalling our visits to Hosmer Lake, I’m eager now to get back to the area and get back on the water again. It’s a beautiful place, and one of my favorite destinations.  Hosmer Lake is located in the Deschutes National Forest. Check the Forest Service

Hosmer Lake is located in the Deschutes National Forest. Check the Forest Service

The following was originally posted on this site a couple of years ago. I checked all of the links, but things can change, so check the

The following was originally posted on this site a couple of years ago. I checked all of the links, but things can change, so check the

If you just want to hang out at the beach, Fort Zach Park has a nice swimming beach (with an adjacent bar). South Beach at the end of Duval Street also has a beach bar and grill. Higgs Beach is four or five blocks east and has a nice beach for sunbathing and swimming. And across the street, Astro City Playground is a fun place for kids to play. To the east of Higgs Beach are C.B. Harvey Memorial Rest Beach (no bar or other amenities) and Smathers Beach. Dog Beach, a couple of blocks east of South Beach, is literally for the dogs – a dog friendly, off leash park.

If you just want to hang out at the beach, Fort Zach Park has a nice swimming beach (with an adjacent bar). South Beach at the end of Duval Street also has a beach bar and grill. Higgs Beach is four or five blocks east and has a nice beach for sunbathing and swimming. And across the street, Astro City Playground is a fun place for kids to play. To the east of Higgs Beach are C.B. Harvey Memorial Rest Beach (no bar or other amenities) and Smathers Beach. Dog Beach, a couple of blocks east of South Beach, is literally for the dogs – a dog friendly, off leash park.

Best Times to Go:

Best Times to Go:

The hike:

The hike:

Other area attractions and activities:

Other area attractions and activities:

Several thousand climbing routes exist within the park, including more than a thousand bolted routes. Climbers literally come from all over the globe to climb here. And an extensive trail system within the park offers hikers a variety of routes of varying lengths and difficulty. Many of the trails are multi-use trails, open also to mountain bikers and horseback riders. Click

Several thousand climbing routes exist within the park, including more than a thousand bolted routes. Climbers literally come from all over the globe to climb here. And an extensive trail system within the park offers hikers a variety of routes of varying lengths and difficulty. Many of the trails are multi-use trails, open also to mountain bikers and horseback riders. Click  Thirty million years ago the area that is now Smith Rock was on the western rim of the Crooked River Caldera. Over time, nearby volcanic eruptions filled the caldera with ash that compacted into volcanic tuff. The tuff was later overtopped with basalt lava flows from vents about fifty miles away. The Crooked River then eroded much of that, leaving the formations we see today.

Thirty million years ago the area that is now Smith Rock was on the western rim of the Crooked River Caldera. Over time, nearby volcanic eruptions filled the caldera with ash that compacted into volcanic tuff. The tuff was later overtopped with basalt lava flows from vents about fifty miles away. The Crooked River then eroded much of that, leaving the formations we see today.

On summer weekends you need to come early to have a chance of finding a place to park. The parking areas fill up quickly, and it’s not unusual to see cars parked along both sides of the road leading to the park and people walking in the road. There has been a shuttle system proposed that would allow visitors to park in the nearby town of Terrebonne and bus into the park, but that (to the best of my knowledge) has yet to be implemented. Even during the week, and on spring and fall weekends, parking can be a problem.

On summer weekends you need to come early to have a chance of finding a place to park. The parking areas fill up quickly, and it’s not unusual to see cars parked along both sides of the road leading to the park and people walking in the road. There has been a shuttle system proposed that would allow visitors to park in the nearby town of Terrebonne and bus into the park, but that (to the best of my knowledge) has yet to be implemented. Even during the week, and on spring and fall weekends, parking can be a problem.

Despite the crowds and other problems, Smith Rock is a Pacific Northwest bucket list destination, not to be missed. It’s a spectacularly beautiful place. But if you’re looking for a wilderness experience, you won’t find it at Smith Rock (except maybe in the middle of winter). If you don’t mind sharing the place with others, though, the park is large enough that visitors tend to spread out, and even at full capacity the park doesn’t feel overly crowded if you get a little ways away from the parking areas. (A recent visitor survey found that 69% of the respondents felt the park to be somewhat to very crowded, however.)

Despite the crowds and other problems, Smith Rock is a Pacific Northwest bucket list destination, not to be missed. It’s a spectacularly beautiful place. But if you’re looking for a wilderness experience, you won’t find it at Smith Rock (except maybe in the middle of winter). If you don’t mind sharing the place with others, though, the park is large enough that visitors tend to spread out, and even at full capacity the park doesn’t feel overly crowded if you get a little ways away from the parking areas. (A recent visitor survey found that 69% of the respondents felt the park to be somewhat to very crowded, however.)

The park is located just east of the town of Terrebonne, which is about 25 miles north of Bend, Oregon, and about 140 miles southeast of Portland. For more information, go to the

The park is located just east of the town of Terrebonne, which is about 25 miles north of Bend, Oregon, and about 140 miles southeast of Portland. For more information, go to the

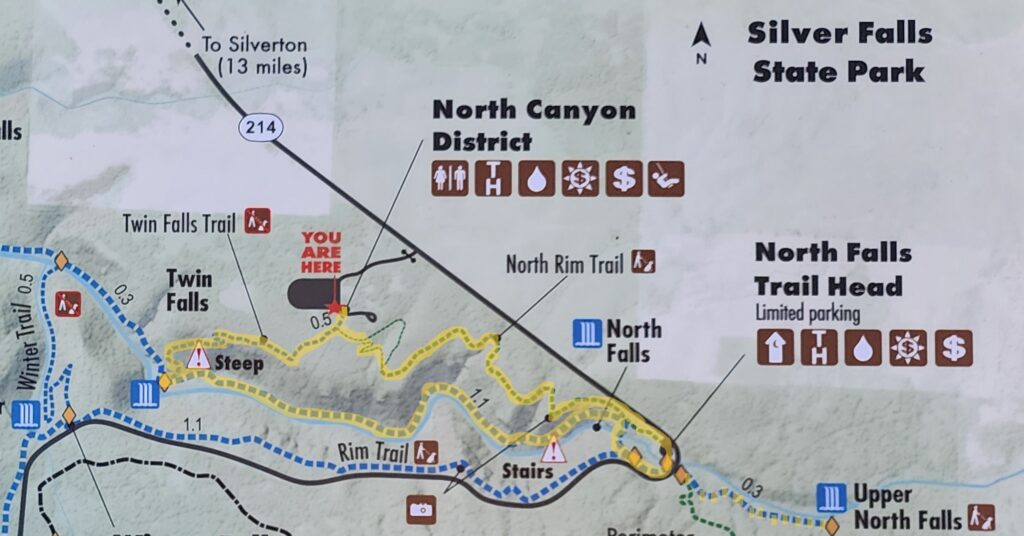

Beyond the Twin Falls Trail junction, the North Rim Trail meanders through the forest, passing a children’s play area and a small two-table picnic area.

Beyond the Twin Falls Trail junction, the North Rim Trail meanders through the forest, passing a children’s play area and a small two-table picnic area.

I have no hesitation in recommending the Isle of Skye as a destination that should be on your bucket list. It’s a wonderful place and Scotland as a whole was a great place to start our explorations in Europe. Scotland is both different enough from the U.S. to be interesting and a bit exotic and alike enough to be comfortable and inviting.

I have no hesitation in recommending the Isle of Skye as a destination that should be on your bucket list. It’s a wonderful place and Scotland as a whole was a great place to start our explorations in Europe. Scotland is both different enough from the U.S. to be interesting and a bit exotic and alike enough to be comfortable and inviting.

For a map of the entire park, click

For a map of the entire park, click

Chehalem Ridge Nature Park is in a rural area with no other close by hiking or biking opportunities, but the west metro area, not far from Chehalem Ridge, has an abundance. Some of my favorite hikes in the area include

Chehalem Ridge Nature Park is in a rural area with no other close by hiking or biking opportunities, but the west metro area, not far from Chehalem Ridge, has an abundance. Some of my favorite hikes in the area include

I love the eroded sandstone rock formations found at Hug Point. The layered sandstone of the point has been warped and folded by tectonic processes and eroded by wind and water into fantastic formations. The tidewater rocks are covered in green algae and seaweed, barnacles, and mussels. The rocks, sand, colorful vegetation, waves, and ever changing light make for great photo opportunities.

I love the eroded sandstone rock formations found at Hug Point. The layered sandstone of the point has been warped and folded by tectonic processes and eroded by wind and water into fantastic formations. The tidewater rocks are covered in green algae and seaweed, barnacles, and mussels. The rocks, sand, colorful vegetation, waves, and ever changing light make for great photo opportunities. Hug Point State Park is located about five miles south of Cannon Beach. The point can also be reached from Arcadia Beach State Park, about a mile to the north. It’s an easy day trip from the Portland area, but there many other attractions in the area, so many visitors spend a weekend or longer in the area.

Hug Point State Park is located about five miles south of Cannon Beach. The point can also be reached from Arcadia Beach State Park, about a mile to the north. It’s an easy day trip from the Portland area, but there many other attractions in the area, so many visitors spend a weekend or longer in the area. The nearby towns of Cannon Beach, Seaside, and Manzanita all have numerous motels, BNBs, and other accommodations, as well as many restaurants and cafes serving fresh seafood and other locally sourced foods.

The nearby towns of Cannon Beach, Seaside, and Manzanita all have numerous motels, BNBs, and other accommodations, as well as many restaurants and cafes serving fresh seafood and other locally sourced foods.

One note of caution, though. If you go, pay attention to the tides. The waterfall and caves that draw most of the visitors to Hug Point State Park are nestled between Adair Point, immediately north of the beach access, and Hug Point itself. At high tide it can be difficult or impossible to get around these two points, so it is possible to get trapped between them.

One note of caution, though. If you go, pay attention to the tides. The waterfall and caves that draw most of the visitors to Hug Point State Park are nestled between Adair Point, immediately north of the beach access, and Hug Point itself. At high tide it can be difficult or impossible to get around these two points, so it is possible to get trapped between them.

Overview:

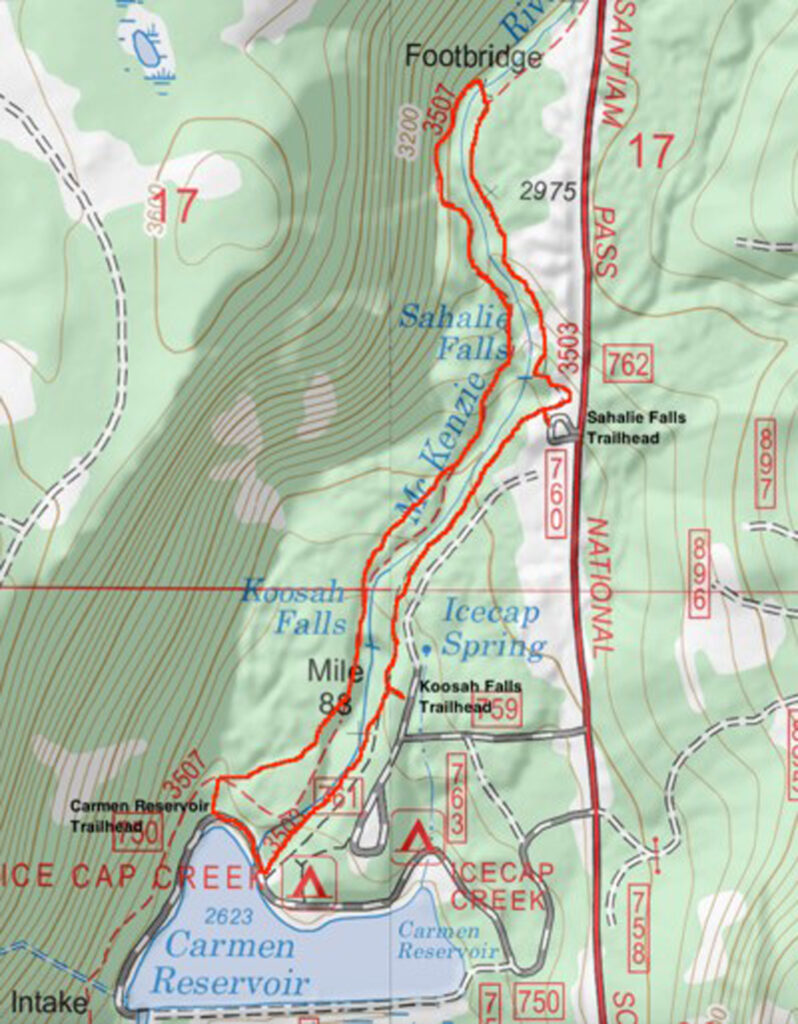

Overview: The history of Lava Canyon begins about 3500 years ago when an eruption of Mount St. Helens sent a flow of lava down the old valley of the Muddy River, destroying the forest and filling the valley with molten rock. Over the intervening years, the Muddy River cut a new course through the lava flow, and the canyon gradually filled with sediment. Then came the 1980 eruption, which melted the summit glaciers and sent a huge lahar (volcanic mudflow) down the valley, destroying the rebuilt forest and scouring out the built-up sediment, exposing the remnants of the earlier lava flow. What was left is a steeply descending canyon with an almost continuous series of spectacular waterfalls and cascades. (For more information on the 1980 eruption, see my

The history of Lava Canyon begins about 3500 years ago when an eruption of Mount St. Helens sent a flow of lava down the old valley of the Muddy River, destroying the forest and filling the valley with molten rock. Over the intervening years, the Muddy River cut a new course through the lava flow, and the canyon gradually filled with sediment. Then came the 1980 eruption, which melted the summit glaciers and sent a huge lahar (volcanic mudflow) down the valley, destroying the rebuilt forest and scouring out the built-up sediment, exposing the remnants of the earlier lava flow. What was left is a steeply descending canyon with an almost continuous series of spectacular waterfalls and cascades. (For more information on the 1980 eruption, see my  Getting there:

Getting there: Trailheads:

Trailheads: The hike:

The hike: Below the overlook, the path is rock and dirt, steep in places. After another three tenths of a mile, you come to another side trail and a suspension bridge over the river that gives a bird’s eye view of the canyon and waterfalls. On the other side of the bridge is a connecting trail that takes you back to the upper bridge, making for a 1.4-mile loop. (Update: As of June 2023 the suspension bridge is closed. Check the National Forest Service’s

Below the overlook, the path is rock and dirt, steep in places. After another three tenths of a mile, you come to another side trail and a suspension bridge over the river that gives a bird’s eye view of the canyon and waterfalls. On the other side of the bridge is a connecting trail that takes you back to the upper bridge, making for a 1.4-mile loop. (Update: As of June 2023 the suspension bridge is closed. Check the National Forest Service’s  At about the 1.3-mile mark, the trail descends a 40-foot ladder to the base of the rock formation known as The Ship. Before 1980, sediment filled the canyon to the top of The Ship, to give you an idea of how much sediment was scoured out of the canyon. A short but steep side trail (and another ladder) leads to the top of The Ship.

At about the 1.3-mile mark, the trail descends a 40-foot ladder to the base of the rock formation known as The Ship. Before 1980, sediment filled the canyon to the top of The Ship, to give you an idea of how much sediment was scoured out of the canyon. A short but steep side trail (and another ladder) leads to the top of The Ship. (Below The Ship, the trail continues another 1.5 miles to the lower trailhead. The entire hike from upper to lower trailhead and back is about six miles and the elevation gain coming back is 1350 feet.)

(Below The Ship, the trail continues another 1.5 miles to the lower trailhead. The entire hike from upper to lower trailhead and back is about six miles and the elevation gain coming back is 1350 feet.) Return from The Ship the way you came. Cross the suspension bridge if it is open and take the trail on the opposite bank to the upper bridge and re-cross the river. The two bridges both give you great views of the river and canyon below.

Return from The Ship the way you came. Cross the suspension bridge if it is open and take the trail on the opposite bank to the upper bridge and re-cross the river. The two bridges both give you great views of the river and canyon below.

Originally posted in a different format September 29, 2018 by Alan K. Lee. Updated and re-posted March 23, 2021. Edited, updated and posted in this format June 29, 2023.

Originally posted in a different format September 29, 2018 by Alan K. Lee. Updated and re-posted March 23, 2021. Edited, updated and posted in this format June 29, 2023.

From the Great Spring the trail follows the east shore through the lava fields and forest. Parts of the trail are pretty rough. Good quality hiking boots are advised, although I did this hike in sneakers on my latest visit. But open toed sandals or flip flops are definitely not acceptable footwear on this section of the trail.

From the Great Spring the trail follows the east shore through the lava fields and forest. Parts of the trail are pretty rough. Good quality hiking boots are advised, although I did this hike in sneakers on my latest visit. But open toed sandals or flip flops are definitely not acceptable footwear on this section of the trail.

Hoyt Arboretum offers a multitude of possible hikes over its 189 acres and 12 miles of trails. The hike described here passes through many of the arboretum’s tree collections and is a good introduction to the arboretum for anyone that has not visited previously. It also incorporates several short sections of the iconic Wildwood Trail that meanders for 30 miles through Washington and Forest Parks. The trail junctions in the arboretum are well signed, so it would be hard to get lost, but the sheer number of intersecting trails can be confusing. I recommend carrying a map of the trail system whenever you’re hiking in the arboretum. Download and print the arboretum map linked above or pick up a free map and brochure at the visitor center. The brochure provides some interesting information and has a larger and more easily read map than the download.

Hoyt Arboretum offers a multitude of possible hikes over its 189 acres and 12 miles of trails. The hike described here passes through many of the arboretum’s tree collections and is a good introduction to the arboretum for anyone that has not visited previously. It also incorporates several short sections of the iconic Wildwood Trail that meanders for 30 miles through Washington and Forest Parks. The trail junctions in the arboretum are well signed, so it would be hard to get lost, but the sheer number of intersecting trails can be confusing. I recommend carrying a map of the trail system whenever you’re hiking in the arboretum. Download and print the arboretum map linked above or pick up a free map and brochure at the visitor center. The brochure provides some interesting information and has a larger and more easily read map than the download.

Trailheads:

Trailheads: